Time for the first in a number of catch-up posts. Since I last wrote the reading has continued apace even as the reviewing has fallen off the cliff.

Fear not, though: I’m not going to subject you to dozens of recaps in one go. I figure five will be more than enough to be going on with (at least until I write up the next five, right?)

Right.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (read by Juliet Stevenson).

My rating: three stars.

I read Jane Eyre a long time ago, and remember a) enjoying it and b) not remembering a lot of it. So when Elizabeth suggested a buddy read, I jumped at it. As I’d read the book before, I gave an audiobook version a spin, largely because I had access to a copy read by Juliet Stevenson, whose work on Middlemarch I enjoyed so much last year.

(Her narration here was, as I had suspected, excellent. Stevenson is pretty much top of my list for readers.)

If you don’t know the work, Jane Eyre tells the story of the titular author from her childhood, though to adulthood and along a series of romances, notably with a Brooding Guy named Rochester. There’s a lot more to it than that – it is quite detailed in its description of a particular style of country life, and tugs at the threads of class and gender more than I had expected – but that’s the broad strokes.

Let’s just say that my take on the book – despite its importance in literary history for its role in progressing the first-person, inner narrative of women – was a bit different that it was 25 years ago. I think the most meaningful (and entertaining) way of conveying this will be to nick comments from the book’s buddy-read chat. They’re pretty indicative of my mindset, and stand alone without textual reference.

Dude’s too tubby to be bringing the beatdown. God I hope he gets completely water-closet dunked at school. What a turd.

Feels like the set up for some panto oh no you’re not oh yes I am palaver.

He is such a fucker. “My little pet” ICK ICK ICK.

I remember enjoying this book years ago but had forgotten it. This section on Rochester The Fuckboi and the poor-me shit, the demands for attention and sympathy even though he’s the dickhead here… remarkably awful. Writing is fine but this whole part is noxious AF and I am surprised at how absolutely furious I am over it.

Dude needs a massive slap. Where’s the cool nanny from the Reed house? She’d oblige.

This section was fucking excruciating. Just go and get dysentery in a land with its own perfectly serviceable religion(s) you fuckhead.

Yeah, look. I still enjoyed a lot of the book, but the collapse of Jane’s character in service of a massive dickhead did not sit well at all. The turn of phrase and the delivery was immaculate, but the narrative certainly gave me a lot more of the ick than it had in the past.

I’m not going to revisit, I suspect.

Providence by Max Barry.

My rating: four stars.

So I follow a guy named John Warner, who writes about books. I very much enjoy his writing, and the fact that his review columns in the Chicago Tribune feature a little bit at the end where readers can write in and tell him their most recently read books, and he recommends something that would appeal.

I wrote to John and he was kind enough to put me in a column, and this, the first Max Barry I’ve read, was the result.

I’ve been reading a little more SF/F than normal over the past couple of years, and I’m getting much more of a taste for it. Providence is a bit more space opera than hard SF, but it’s an intriguing look into the lives of a crew aboard a ferociously-armed warship, who – alongside their other tasks – have to file social media reports in order to keep the billions back on Earth appraised of the worth of their alien-hunting expedition.

“Gilly, there’s another really important reason we’re out here,” Beanfield said. “We’re a humanizing media presence.”

What results, while it involves a bunch of bug-squishing, target-acquired tense moments, turns into a considered rumination on what makes us us, and on the malleability of reality.

I’m not going to expand on that, as the book is a quick read, and if your interest is piqued by the concept of having an identity crisis in space, I reckon you’ll dig it. I did, and will certainly look for more Barry for the future (fittingly).

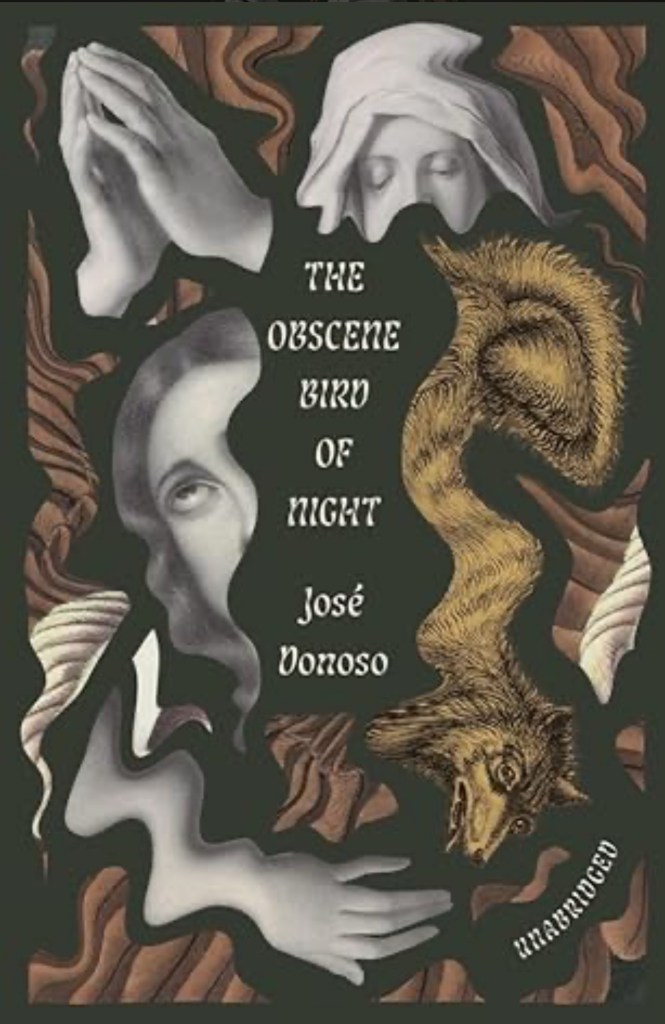

The Obscure Bird of Night by José Donoso (tr. Leonard Mades, Megan McDowell and Hardie St. Martin).

My rating: four stars.

I preordered this newest version of The Obscure Bird of Night because it’s the sort of thing that is ferociously expensive (assuming you could find a secondhand copy anywhere) and because this edition presented the work in full, replacing 20 pages that had been snipped out during its publication in English in the early ’70s.

The book is a high-water mark of magical realism, a genre that I’ve previously dismissed as being a bit twee, or in the misguided belief that things need to be REAL in order to be meaningful, and it has single-handedly made me reconsider my stance.

(If you’ve any magical realism recommendations, please let me know.)

Donoso’s text is dense and excessively weird, coiling upon itself in a perversely appealing manner. You’re never entirely sure what’s going on, and there’s the distinct feeling that by not reading it in the original, you might be missing something, though I suspect that feeling of being all at sea is authorial intent rather than a knock against the easily-read translation. I didn’t know what the fuck was going on for stretches of time, until something would knock into place and whole chunks of narrative reveal their structure as if lit up from a distance. It’s a remarkable piece of work, but I don’t know that I can surpass the back-of-the-book blurb in terms of giving you an idea of what’s held within.

Deep in a maze of musty, forgotten hallways, Mudito rummages through piles of old newspapers. The mute caretaker of the crumbling former abbey, he is hounded by a coven of ancient witches who are bent on transforming him, bit by bit, into the terrifying imbunche: a twisted monster with all of its orifices sewn up, buried alive in its own body. Once, Mudito walked upright and spoke clearly; once he was the personal assistant to one of Chile’s most powerful politicians, Jerónimo de Azcoitía. Once, he ruled over a palace of monsters, built to shield Jeronimo’s deformed son from any concept of beauty. Once, he plotted with the wise woman Peta Ponce to bed Inés, Jerónimo’s wife. Mudito was Humberto, Jerónimo was strong, Inés was beautiful–once upon a time… Narrated in voices that shift and multiply, The Obscene Bird of Night frets the seams between master and slave, rich and poor, reality and nightmares, man and woman, self and other in a maniacal inquiry into the horrifying transformations that power can wreak on identity.

Now, star translator Megan McDowell has revised and updated the classic translation, restoring nearly twenty pages of previously untranslated text that was mysteriously cut from the 1972 edition. Newly complete, with missing motifs restored, plots deepened, and characters more richly shaded, Donoso’s pajarito (little bird), as he called it, returns to print to celebrate the centennial of its author’s birth in full plumage, as brilliant as it is bizarre.

There are two kinds of people in the world: people who’ll read that and nope out immediately, and people who will fuck yeah their way into an immediate order. As one of the latter, I can tell you that reading this work is definitely better than the joy of knowing that there exists something as bonkers as is described above.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs (read by Donna Rawlins).

My rating: four stars.

Another surprise packet. Jane Jacobs’ work on urban planning and its ills was first published in 1961, and I’d heard it mentioned as one of the leading books on the topic. Jacobs was an activist with skin in the game: she had no architectural training, but being a longterm New Yorker (Greenwich Village, specifically), she had a love for the metropolis. When her neighbourhood was threatened by Robert Moses’ roadway-and-reclassification plans, she took up rhetorical and organisational cudgels against the political titan.

We expect too much of new buildings, and too little of ourselves.”

That story is covered in pretty good detail here, and The Death and Life of Great American Cities is a still-relevant examination of how cities (admittedly of a very specific type) work, and how they require congenial planning approaches to continue to thrive. I listened to a lot of this book while riding my lawn mower, and was continually struck by how, six decades later, Jacobs’ thoughts were applicable to city life today.

Being human is itself difficult, and therefore all kinds of settlements (except dream cities) have problems. Big cities have difficulties in abundance, because they have people in abundance.

Is the book flawed and outdated? To a certain extent. It can be dry and heavy going (as some reviewers note), and it is convinced of its own worthiness a little much. Jacobs chucks in to be sure about as regularly as paragraph breaks. Planners have found holes in lots of the arguments, and undoubtedly the approach towards public amenity and sustainability of cities has changed a lot since the days of Moses et al. But what’s in here is a reminder of the great joy that the city as home can bring to its inhabitants and visitors, and stands as a testament to the great love story between author and subject.

Automobiles are often conveniently tagged as the villains responsible for the ills of cities and the disappointments and futilities of city planning. But the destructive effect of automobiles are much less a cause than a symptom of our incompetence at city building.

Jane Jacobs: city-dwelling bad-ass. That’s enough reason to give this a go.

The Second World War by Antony Beevor.

My rating: four stars.

I moved schools (and countries) during my high school career, and for one reason or another I never took any Modern History classes. So for the longest time, my knowledge of the Second World War was based on things I could cobble together from TV documentaries, films, and discussion. I had a loose idea of what had happened and how it had happened (though ultimately a lot of my knowledge came from playing Battlehawks 1942, a Pacific theatre flight sim) but it wasn’t the most nuanced view of history around.

A few decades later – and after earlier rectifying my WWI ignorance – I finally got around to finding out what it was all about. (TLDR: grain and the fact WWI never really ended properly. Oh, and racism. Always racism.)

Saying that, this note appears early and seems curiously appropriate now, which is… less than ideal.

In the face of financial disaster, the authoritarian state suddenly seemed to be the natural modern order throughout most of Europe, and an answer to the chaos of factional strife.

Ahem. (Also: seems like not enough people read Smedley Butler’s book before this shit all kicked off. Could’ve saved us all a bit of strife if War Is A Racket got as much of a look-in as Mein Kampf, I guess.)

Right, so what we get in this volume is a necessarily brief description – by which I mean “not bogged down in the mechanics-of-war minutiae that Dudes of a Certain Age appear to enjoy” rather than “lacking detail or rigour” – of the events that unfolded across the world from 1939–1945. Beevor moves from theatre to theatre, drawing connections between political relationships across hemispheres to inform the reader of the broader causes and effects of governmental and military action. It’s not dumbed-down, but it’s also not at policy wonk level: the copy is dynamic and relatable, and doesn’t require continual map orientation to be understandable.

One thing that sticks out to me – as it did with my reading about the First World War – is the sheer number of bodies involved in the battles, and the ruthlessness exhibited by people at the extremest edges of experience and survival. The losses involved – and in many cases, prompted by machinations of leaders with little solid realistic knowledge, or care about their charges – were absolutely staggering, no matter what the side.

In that one month of January 1945, Wehrmacht losses rose to 451,742 killed, roughly the equivalent of all American deaths in the whole of the Second World War.

Of course, it wasn’t just the death of troops (and of civilians) that prompts some what-the-fuck, it’s the spectre of the mental damage that such involvements incurred.

The surgeon-general of the US Army estimated that American front-line forces suffered a 10 per cent rate of psychiatric breakdown.

The psychic strain of events on combatants and noncombatants alike is a particular focus for the author, who takes pains to use contemporaneous sources from all sides, which reveals that when the us vs them rhetoric of leaders is stripped away, soldiers of all stripes (and those dealing with soldiers) went through similar experiences. (And, surprisingly – though perhaps not too surprisingly – committed similar atrocities.) There’s a distinctly humanising motive at work through the book, though it can be very difficult to reconcile events such as the Rape of Nanking or the ruthless efficiency of the death camp system with anything even approximating humanity.

Ultimately, the story of WWII is incredibly complex and incredibly simple. It’s about people fucking over people at differing scale. And while I believe there’s a lot more still for me to learn – and undoubtedly different historians will hold different interpretations of these events – Beevor’s work has succeeded in telling the stories of this agglomeration of battles while sparking a desire to know more.

If you’re after some good bookish times, please check out my profile on TheStoryGraph.

If you’d like to buy me some books to review, there’s a wishlist over here.

[…] was that a book discussing Robert Moses could have been printed without referring to Jane Jacobs. I’d listened to her landmark book earlier in the year, and was surprised by the omission of her battle with Moses over roads through […]