This one has been sitting in the draft pile for a while. Over the Easter and Anzac Day break I managed to plough through a few books, a breather following a work trip to Sydney for some in-office reviews and woodshedding just before.

Since then, there’s been more work trips, and a truly hellish deadline with a whole lot of out-of-hours work going on. While that was going on, my desire to read (let alone write) has cratered. Which honestly, hasn’t been great for me: think of it as being hangry, only about reading. When I can’t read – can’t being the operative word here, given the amount of hard screen edits I’ve been doing, to the point that I just need to defocus at the end of the day instead of chowing town on some tasty tomes – I feel discombobulated and Not Quite Right.

So anyway, here we are. I’m having a couple of days off as recharge days, and am hoping to push through some more books. And catch up on my diary. And finish this bloody post.

If you’re reading this, I guess we did it.

Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground by Michael Moynihan and Didrik Søderlind (reread).

My rating: three stars.

I was sent a copy of this from my Amazon wishlist years ago (before the revised edition came out, I believe) and I dived in because a) I knew fuck all about black metal back then and b) I wanted to figure out what the story was behind the lurid headlines surrounding the early Norwegian scene that involved Mayhem (the band), church-burning mayhem (not the band but involving the band), self-mutilation, suicide, murder, cannibalism, tape trading networks and much deriding of posers.

We do not claim to offer any cut-and-dried rationale for why these events all happened, or continue to happen. There is no simple or single answer.

Basically, it was insufferable but had some cool albums result. If you’re into black metal (which I am, kinda sorta) it’s a period of terrible audio quality and wicked (in manifold senses) songs. If you’re not, it’s a pissing contest involving dudes with lank hair who all seem to hate each other but desperately want to appear cool (kvlt!) to each other. But to not look like they care, because caring is very unkvlt, dvde.

I guess after the first church burned down in Bergen, people got very enthusiastic about it.

Anyway, at the time I remember that the book felt a bit like a loose assortment of essays rather than a cohesive book, and that take hasn’t really been ameliorated by the second edition’s additions. What stuck out to me more, as well, were the criticisms of one of the authors (Moynihan) for his focus (positive, kind of) on Varg Vikernes, a convicted killer who now is free and freely Nazi-Odinist on multiple platforms.

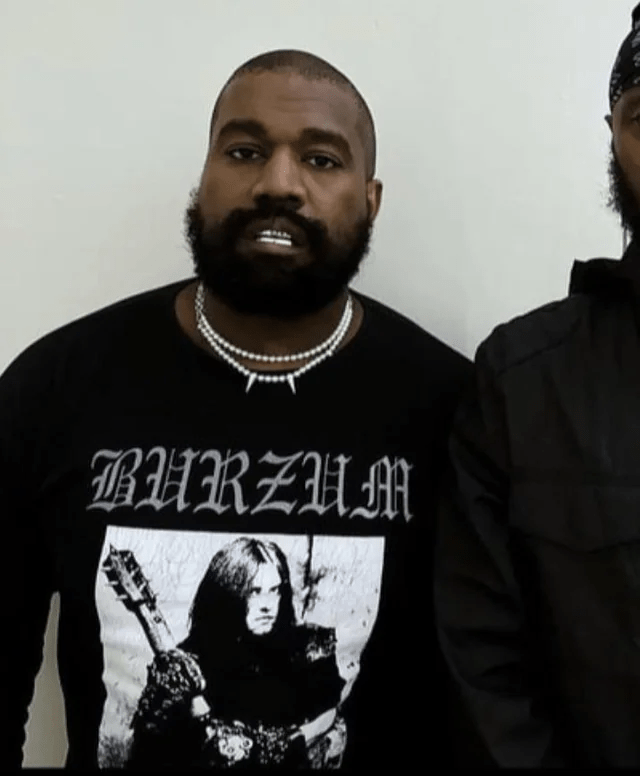

You know, the guy behind Burzum, whose shirt the downward-spiralling Kanye West spruiked in the lead-up to where we are now, the timeline where he releases a tune called ‘HH’ on VE day which features not only the predictable straight-arm shout-out, but also a Hitler speech sample.

(At least he’s just burning his career down, I guess. Though the year is yet young.)

Yes, that would be the worst timeline.

Back to the book. There was a lot of unquestioned shit-takery throughout the book that I felt didn’t do anyone involved any favours. Varg gonna Varg throughout, to the extent that it’s suggested that his burning of churches throughout the land (sorry, alleged burning of churches) was the same as Northern Ireland’s experience of protest against British invasion of spiritual sanctuaries. (!) Which felt like quite a hamstring-pulling stretch to me.

I don’t know, perhaps I’m Less Tolerant of Bullshit but while the read reminded me of the story at its heart, it didn’t seem to engage particularly much beyond pointing and saying “See! See how grim this is!” which isn’t enough. While there’s not strict endorsement of anything that went on, there’s also not a sense either of the authors calling the participators on their shit. Or for calling out the homophobia, racism, antisemitism and so on out for what it was, rather than chucking a blanket of artistic misanthropy over the whole bunch of battle-vested fuckheads. There’s not a lot of conclusion, and partway through, once I’d gotten over the shock of being reacquainted with some of this heinous shit, the big “but why bother?” question kept coming to mind.

(Erik from Ulver calling black metal fans losers was the only real kvlt thing that occurs throughout.)

There’s been a movie made taking this book’s action as its basis. I thought it was all right, but then that’s probably because I’m a poser and not trve kvlt. (Which is fortunate, as that sounds like altogether too much hard work, what with the writing of your own shitty ttrpg game and all.)

The Enterprise of Death by Jesse Bullington.

My rating: four stars.

A decade or so ago I read Bullington’s first (?) book, The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart which was an excessively grotesque piece of adventurous filth that I very much enjoyed, while (most of) my fellow book club participants did not.

The Enterprise of Death sat on my Kindle for quite some time, but the aforementioned trip to Sydney had me dig it out for a bit of in-transit entertainment. Happily, Bullington’s love of the gothic and grotesque had not diminished between tomes. If anything, it’s kicked up a notch and given a pestilential smock to show off with.

The animated corpses stayed outside.

The novel takes several real people – notably lead character Niklaus, a sometime soldier and artist – and releases them in a tale of necromancers, witches, lesbians, lesbian witches, the undead and general 16th Century debauchery and European warfare. It is an extensively researched and finely detailed setting we’re cast into, and while the story is ostensibly a fantasy, there’s a layer of realistic dirt that acts as a bulwark against moments that’d typically have the reader cry bullshit on the proceedings.

We are born into this. There are none, none, who escape the fact that in our very nature is a compulsion to annihilate ourselves. And each other.

It’s delightfully grotty and thoroughly engrossing. There’s honour amongst thieves, whores’ glory and a genuine sense of outsider power, all in a setting that would qualify as grimdark if it wasn’t set in a world that’s mostly tied to realities of history and geography.

That is to say: this is worth reading. If it sounds even vaguely like your kind of thing, I’d suggest that you’ll enjoy it immensely. I’m amazed it hasn’t been adapted yet.

The Solid Mandala by Patrick White.

My rating: five stars.

Back on my Patrick White bullshit as I try to work through his published works after having a whole Damascene revelation as to his skill on my second run-through of Voss. (The first was at uni, I sucked ergo I thought it sucked.)

Anyhow, The Solid Mandala is White’s seventh novel, released in 1966. It’s the story of twin brothers – the erudite Waldo and the developmentally challenged Arthur – who live in a thinly-disguised Castle Hill. The story is told in four parts, with a section given to each brother, with outsiders’ views both setting the scene and closing the action.

There was an occasion when Dad put down the book and said: “Sometimes I wonder, Arthur, whether you listen to any of this. Waldo can make an intelligent comment. But you! I’ve begun to ask myself if there’s any character, any incident, that appeals to Arthur in any way.”

The story is seemingly straightforward: it’s a tale of sibling rivalry, life and love, told in White’s ocean-liner pacing (slow, difficult to turn around, intent on going where it’s going, currents be damned). The brothers live together as old men, with Waldo shepherding both his brother and their dogs through a conjoined life with an element of sullen duty. There’s interruptions of the outside world into their life, but largely it’s viewed in terms of us and them (or more appropriately, me and them) rather than in a holistic manner. And until I hit Arthur’s section, I thought the book was good but not great. It had talked about Waldo’s frustrated dreams, his smart kid’s inability to fit in, to find love, to do something with his life beyond library work that didn’t engage, and sure, that portrait of a frustrated existence is the sort of thing I’m normally all about, but it didn’t seem to be anything much out of the ordinary.

But the Arthur section? Immediately kicked this one from a solid three to a five. Forgiveness of the age’s presentation of developmental delay as being simple notwithstanding, what’s presented was a piercing display of protective love. While the sense of still waters running deep might be a hackneyed trope, it was entirely suitable here, and elevated the work. Arthur’s thoughts and interpretation of the world were backed by that polished-diamond clarity I enjoy so much in White’s writing: a sense of seeing all, of capturing the moment so clearly and effortlessly.

Waldo kept looking round to see who might be noticing. As for Arthur, he did not care. Their relationship was the only fact of importance, and such an overwhelming one.

It’s a story of what happens when we’re not looking, the secret narratives that we continually replay and take into ourselves to make our lives manageable or to give them meaning. I was surprised at how touching some of the revelations within were, and of how the titular image – so deep, yet so simple – was just the perfect representation of the idea of a life’s fixed point, however much it might refract and reflect.

This was a delight to read, and it reminded me that I need to read much more of the man’s work, the ridiculously talented bastard.

The Electrical Experience by Frank Moorhouse.

My rating: three stars.

This is the first of Frank Moorhouse’s books I’ve read, which is vaguely suitable as though it’s only novella length, it seems to be his first published novel, coming in 1974. It’s also the sort of thing that Noted Book Wankers would probably enjoy, as it’s sliced into pieces, with inserts detailing the preoccupations of the book’s main character, T. George McDowell including much on the making of soft drinks (McDowell’s trade) and ice (the refrigerant, not the gee-up stuff).

The book’s subtitle – a discontinuous narrative – is suitable, as the story jumps around. It’s the story of a man of the century, of generally withheld opinions and generally trumpeted nous who is compared in the course of the book with his out-of-control daughter Terri.

I do not care for words in top hats. I believe in shirt-sleeve words. I believe in getting the job done. We’re like that on the coast.

Terri represents everything McDowell is not. He is a Get Things Done kind of fellow, while Terri is what could most charitably be called a loose unit, though her interactions with the representative of a multinational drinks company (fucking him) will turn out to be more profitable than the interactions her father will likely have with them at the close of the novel (fucking him and his business).

This is a book about tradition, told in a way that would likely challenge those seeking a traditional reading experience. The old guard of Australia is examined intensely, caught on film and poked and prodded by the younger generation to reveal its inherent hypocrisy and uselessness. It’s at once parochial and expansive, and has spurred me to pull down some more Moorhouse. If he can do this in under 200 pages, what’s he like at full stretch?

Serendipitously, I read this while I was on the South Coast of NSW, its setting. I can’t explain it, but the text felt very suitably South Coast, even though I can’t put my finger on why.

The Well by Elizabeth Jolley (reread).

My rating: four stars.

I read this a long time ago, probably around the time the much maligned film version was released. I remembered nothing about that reading, and I think upon reflection I’d somehow lumped it in with Tim Winton’s In the Winter Dark, largely because a) the film version of that came out only a year later and b) both of them feature Miranda Otto.

Anyhow, the same sort of it’s grim in the country vibe is shared by both tales, though this one is much more predicated on humans as the prime movers of grim shit rather than some kind of wild beast or supernatural agent. We’re presented with a view of the life of a middle-aged woman, Hester Harper, who brings a John Travolta-loving orphan, Katherine, into her home. Harper is a Woman of Means in the community, a large landowner, but has no real connection of her own beyond those that come with being a large landowner: respect due, but not especially earned.

The delightful thing about Katherine was that she grabbed life with both hands. She wanted all the life as she saw it in films. She wanted adventure and Hester was drawn into this wanting.

What results from this new living arrangement is a relationship with stunted emotions, a weird balance of power, and a dislike of washing up (to the point of chucking dishes down an abandoned well). Things proceed in a queer-coded, unrequited love/living representative of what-I-could-have-done-if-only way until Katherine hits something with the car on the way back to the farm late one night, and the two women have to cover up the event, placing .

Distinctly ’80s Lady Macbeth vibes result. Katherine does not handle things well, while Hester handles things the same way she does dirty dishes: by putting it down the well. Ghostly voices (or are they the voice of conscience?) echo across the dark nights, and the remote nature of the pair’s lives leads to unbearable tension, at least in terms of the survival of things as they are.

I enjoyed the book as portraiture, but can’t say the story was particularly compelling. It read a little bit like a fleshed-out play rather than a novel; there was the feeling that blocking and staging weren’t far from the author’s mind. I’m not sure what else was up for the Miles Franklin in 1986 (I can’t seem to find a longlist anywhere?) but I’d be interested to know in order to compare: was this the best there was that year? Again, enjoyable, but not particularly memorable, as detailed as the lonely sketches within may be.

I can also provide another reader’s view of this book, a rarity in the reviews here. Eve finished her books while we were away at an off-grid cabin, and this was the least wanky of the stack I’d taken. She read it and said it was intensely irritating: unlikeable people doing stupid things until an ending of no point was reached.

(Look, she’s not wrong. I just happen to enjoy all that stuff, which is probably a cautionary concern.)

If you’re after some good bookish times, please check out my profile on TheStoryGraph.

If you’d like to buy me some books to review, there’s a wishlist over here.