Not much in the way of preamble, now: here’s another tranche of book reviews. Delighted that they all were cracking reads, which I assume means I’m going to read an absolutely terrible piece of shit next as some kind of literary karmic revenge.

We’ll see.

(Although I’m already reading something that’s a three-star at best so hopefully I can channel all the due shittiness into that one and thus escape any more dire reads than are absolutely necessary.)

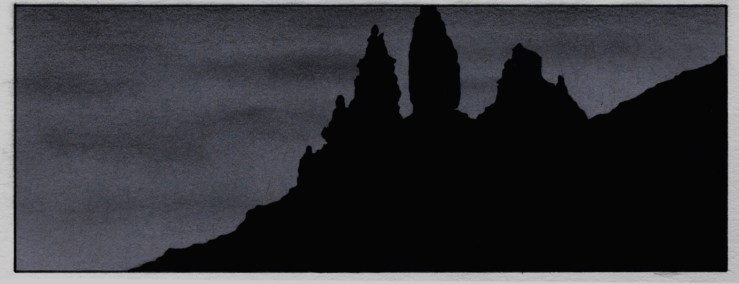

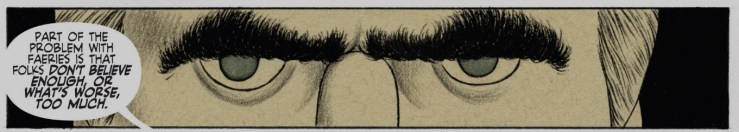

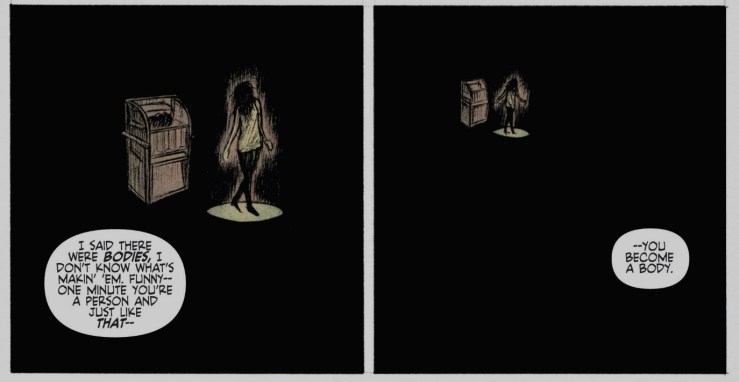

Double Walker by Michael Conrad and Noah Bailey (artist).

My rating: four stars.

The first graphic novel I’ve read this year, Double Walker is a self-contained blast of loss and folk horror. Set in the Scottish Highlands, it follows a couple – Cully and Gemma – making one last trip to the wild island location of The Storr before their child is born.

Hikes are planned, and the fresh air and rugged surrounds are meant to serve as a tonic, a sort of celebration of the couple’s life together before everything changes.

Things change, but not in the way that’s expected.

A simple walking tour results in tragedy, and that loss seems to cast a pall over the village where Cully and Gemma are staying. Bodies begin to appear, and it seems that some heinously bad shit is occurring again, much to the chagrin of the local detective.

The prevailing feeling of the work is of something by David Lynch or Robert Aickman. It’s small-town folk horror coloured by incredible, mind-breaking loss. The powerful hold that tragedy can have on an individual seems to power the natural world’s tendency towards that whole brutish and short idea of existence. It’s a slight tale, but it’s one that does precisely what it needs to, giving a cloying sense of an awoken, ancient and unbearable pressure.

Double Walker pretty remarkable, especially when you consider how finely detailed the artwork is: it feels much more like a sepia-toned storybook, laboriously illustrated with careful pencil work and excellent blocking. It’s work that I’m keen to see more of, as I found its mannered chills particularly engrossing.

Beethoven’s Assassins by Andrew Crumey.

My rating: four stars.

Crumey flew under my radar until recently. I saw his name on some Dedalus books and thought that he might be of interest, because I’ve yet to come across a dud in their range thus far.

(That and I like to pick them up whenever I see them because there’s a certain element of oh-I-found-treasure! occurring whenever I see one in Australia: i.e., a lot more rarely than I’d prefer.)

But the blurb for Beethoven’s Assassins sealed the deal:

Simultaneously a touching human story, a meditation on art and science, and a primer on Beethoven’s life and work, Andrew Crumey’s ninth novel skilfully weaves history, music, erudition and humour in a page-turning mystery that will resonate in the reader’s mind long afterwards.

A lost opera and a dark conspiracy lie at the heart of this philosophical comedy which views Beethoven through the eyes of multiple characters across time, linked by strange events at a rambling country house. Nowadays a retreat for artists, scientists and researchers, the house was formerly an asylum with a clairvoyant inmate, and before that, a location for esoteric experiments. As labyrinthine as the architecture is a plot whose themes include Crusader legends and 1920s literary London, mesmerism and freemasonry, psychoanalysis and theosophy. Holding everything together is a present-day scholar whose pandemic disasters propel him into the byways of history and towards an untimely demise.

You should really stop reading and go pick it up yourself, because it’s all that and more. There’s a self-insert author/writer who’s dealing with pandemic and parental decease, a series of mysterious artist residencies, testimony from ole Ludwig’s sister-in-law (shocked at his scrawling on the walls, I tell you) and some strangely psychogeographical fuckery taking place.

(Oh, and some excellent Maugham bashing.)

Maugham was one of the most successful and admired English writers of the first half of the twentieth century, then suffered the typical posthumous eclipse when fashions change, though a couple of his novels are still widely remembered, if not much read. The Magician isn’t among them.

There’s the risk that a book with so much in the air (multiple narratives across centuries, linked in mysteriously opaque ways) could disappear up its own arse, but Crumey carries it off well. It’s a shaggy dog tale, but so’s pretty much everything Umberto Eco writes, and he’s lauded as fuck.

Seeing connections everywhere is a hallmark of madness as well as German Romanticism

Big recommend. It’s funny, has excellent musical knowledge and feels exciting, honestly.

The City & The City by China Miéville.

My rating: four stars.

In the introduction to this book, Miéville namechecks a series of authors (Raymond Chandler, Franz Kafka, Alfred Kubin, Jan Morris, and Bruno Schulz) stretching across history, weirdness and straight-out noir. What he’s created with this novel is a fully realised synthesis of all of them: a dark detective story that’s set in a city where Cold War Berlin divisions have taken up residence in people’s heads as well as their streets.

I always wanted to live where I could watch foreign trains.

It occurred to me that the author has a bit of a Tolkien thing going on: the titular city/cities have multiple languages and cultures. The text is salted with loanwords, and there’s a history – not to mention archeology – that’s well realised. This feels like a living place. It’s a bit labouring-under-communism, a bit down-at-heel Europe, a bit tech-investor capital. And it’s here, where each side of the city fastidiously ignore the existence of the other, that a murder drags Borlú, a detective, across boundaries to uncover the identity of a murder victim.

‘What’s their office like?’

‘Like ours with better stationery. They took my gun.’

Before long, Borlú needs to look beyond his own beat – no matter how much that feels unnatural to him – to solve a crime that grows more involved the more he looks. What results is something that evokes cobbled streets and Carol Reed direction: at once historic and full of potential.

I’ve always had Miéville on my TBR list, and if this is any indication, I’ll be ploughing through more of his stuff soon. The City & The City is a propulsive tale with enough depth to ensure that there’s something for anyone, whether they’re reading for pulp or philosophy.

Vineland by Thomas Pynchon.

My rating: four stars.

This is another book I’ve had on my shelf for the better part of thirty years. I picked up a copy while I was living in London, based on how much I enjoyed both The Crying of Lot 49 and Gravity’s Rainbow, both of which I’d read at university. And on the shelf it stayed until, prompted by my mate Russ’s rereading of the novel, I decided to give it a go.

(Could it also be said that my desire to read it was also boosted by knowing that Paul Thomas Anderson’s next film is based on the book? Well, yes given how much I enjoyed his adaptation of Inherent Vice.)

What we get is a wild Reagan-era tale of Californian excess and culture war, which is pretty much par for the Pynchonian course. It involves proto-Dude Zoyd and his daughter Prairie avoiding the attentions of nutcase agent Brock Vond, who has Reasons To Be Fucking With Zoyd. Those reasons (and the backstory of all) are explained in what follows. Most of which revolves around Prairie’s mother, Frenesi, a mysterious reactionary and member of a militant filmmaking collective.

Zoyd remembered her…as a tall florid girl in a minidress that bore the image, from neck to hemline, of Frank Zappa’s face, thus linking her in Zoyd’s mind somehow with Mount Rushmore.

Needless to say, hijinks ensue.

The story is firmly what you’d expect: trenchant observation wreathed in dayglo bongsmoke. The general vibe of earlier works is continued and expanded – we finally get to meet Mucho Maas, the husband of The Crying of Lot 49‘s Oedipa – and though it lacks the heft of something like Gravity’s Rainbow, it feels no less meaningful for all that.

Fortunately Ralph Wayvone’s library happened to include a copy of the indispensable Italian Wedding Fake Book, by Deleuze & Guattari, which Gelsomina, the bride, to protect her wedding from such possible unlucky omens as blood on the wedding cake, had the presence of mind to slip indoors and bring back out to Billy Barf’s attention.

(There’s way more songs than I remember appearing in his other books, though. Some things don’t change.)

I don’t know what I expected going in, but I was pleased with how the book unfolded. It’s had a reputation for being Pynchon lite, but that strikes me as unfair: Vineland is as reined in as one might expect the conspiratorial hippie narrative to be, and it all ties up pleasingly. It’s nice to be surprised by a work, especially from someone who you think you’ve got a grip on.

How will the adaptation go? I’m yet to be convinced, though I do find the trailer promising, even if it is an updating of the story from its literary setting.

Here’s hoping old Thomas makes a cameo, paper bag and all.

(Also, can I just get a fuck yeah for the news of a new Pynchon book? Due in October, folks.)

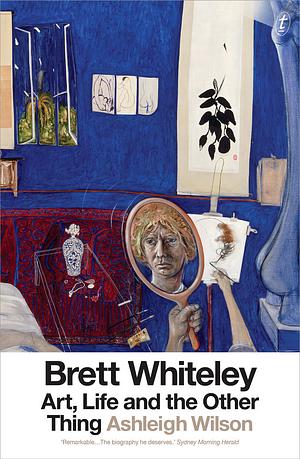

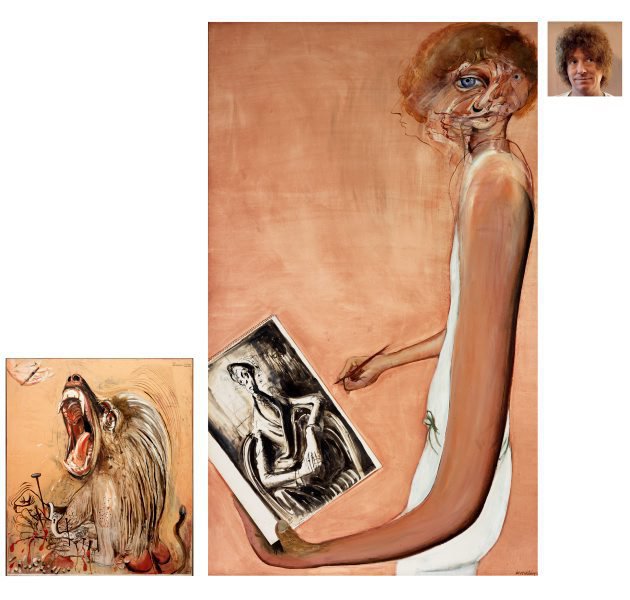

Brett Whiteley: Art, Life and the Other Thing by Ashleigh Wilson.

My rating: five stars.

I bought this book on a visit to the AGNSW just after it came out and it sat on my shelf until last week. Why last week? The Orange Regional Art Gallery was, it turns out, the only non-AGNSW gallery to host a Whiteley exhibition that’s travelling around while the artist’s studio is under renovation. Seeing such high quality, thrilling work in person reminded me that I had the book (and that I only knew the briefest outline of his life), so down it came.

Wilson’s writing is engaging, and a lot of the book’s content appears to have come from voluminous correspondence with the artist’s family and contemporaries. It lacks the occasional stilted academic nature that often dogs artist biographies, though this is not to say it’s a sort of Hollywood Babylon kind of gossip-fest, either. What we have instead is a considered work that captures the man’s curious seesawing between playfulness and self-destruction.

Whiteley’s life – from Sydney’s north shore to its end in a Southern Highlands motel room – is told without judgement, but with acknowledgement of how tempestuous the times he created in were. Central to the story, of course, is Wendy Julius, who Brett met at 17 (she was 15) and who became his muse, his wife, his partner in addiction and his longest champion, despite their acrimonious divorce.

His ‘little world [had] crumbled’ without Wendy. It was not a ‘sex or ego drive’ that demanded her presence; he just could not ‘conceive a better mate right now’. Florence lay ahead but Brett was feeling purposeless. ‘The entire motivating force has been Wendy-her coming, us looking + searching together. Every gallery, every street has been explored with the thought of showing them to her.’

It is clear from the outset – when Brett worked in an advertising agency before going all-in on the international art life, thanks to a Russell Drysdale-judged art scholarship – that he drew an almost mythic energy from Wendy.

In Lavender Bay, Brett had his sights set on a teenage girl who lived a few doors away. Both he and Wendy knew her parents, and Brett was open about his pursuit. He even approached the girl’s mother with an idea: the girl was going to lose her virginity somehow. It could be to the local plumber, so it might as well be to him.

(This did not stop him rooting around on her, however. Also, regarding the quote above? Fuckin’ gross.)

Brett and Wendy (and eventually their daughter Arkie) spend time in cities across the world, cultivating friendships with artists, musicians and random dealers. It’s a who’s-who of the counterculture, which I suppose is what you’d expect from someone who lived in the Chelsea Hotel when Janice Joplin was in residence. Bob Dylan crops up repeatedly, as does Dire Straits. Francis Bacon, whose influence on the younger artist was profound, features in several tales of piss-artistry and friendship. (The drinking I’d expected, but the friendship – as I’ve learned from several Bacon biographies – is a true mark of the elder artist’s esteem: he wasn’t known as Old Cunty for nothing.)

A lot of space is given over to the development of Whiteley’s art, and the seemingly immediate success he attained during his initial stint in London. The development of both abilities and thoughts behind the art – handily explained through copious letters and artist scrapbooks – give great insight on how he viewed the world, or how he tried to convey his take on matters both political and esoteric. As a bit of an antenna picking up the social wavelength, it’s no surprise that Whitely eventually tunes into heroin in a big way.

From here, the story enters the familiar spiral of addiction, recovery, relapse and recovery. Dark clouds form over the Lavender Bay house where the couple lived, and it’s something that never really lifts, no matter how much Whiteley tried. (It’s suitable that this book takes its title from Whitely’s 1978 Archibald-winning triptych, where he publicly confirmed the poorly-kept secret of his addiction in a Baconian blast of pain.)

It’s a sad tale, for sure. One feels sorry for Wendy, especially, but also for Brett, struggling with the inability to say as much as he wanted to. Of course, this is tempered by the incredible achievements he attained throughout his career – multiple prizes, incredible riches, and the friendship and esteem of some of the world’s greatest artists. I learned a lot from these pages, and the story I thought I knew turned out to be a lot richer than I’d imagined.

(Aside from the practical biographical purpose of the book, it provides a great sketch of Australia from the 1950s to the 1980s: parochialism under attack! I feel I know a bit more in general about the period, as well as about Whiteley in particular.)

Brett had been looking forward to watching films, but the quality was poor and censors cut into the few good ones. The country was affluent but empty. There were ‘very bad vibs everywhere’ and ‘fuckin sheep everywhere’. It gave him a new respect for America.

Reading the book I kept thinking about seeing the pieces in the flesh so recently. It meant that when Wilson discussed specific canvases, I could relate. The works seemed more alive because I’d seen them so recently and discovered the circumstances of their creation. It’s certainly something that bolstered my enjoyment of the book, and let me see more clearly what the author was on about.

Jump in. This story is excellent (and a real fucking tragedy).

If you’re after some good bookish times, please check out my profile on TheStoryGraph.

If you’d like to buy me some books to review, there’s a wishlist over here.