So we’re almost three weeks into 2025 and it’s been… meh? I suppose that’s how most people view this part of the year: if you work in an industry that has a Christmas shutdown, you’re in the position of a car that’s driven daily then left alone while its owners go overseas for a bit: when they get back, it doesn’t roar back into life with quite the same aplomb.

Things groan. Starting becomes a little more of a trial than it had been. Things will, with a bit of coaxing and care, get back to proper running once more. But it’s gonna take time.

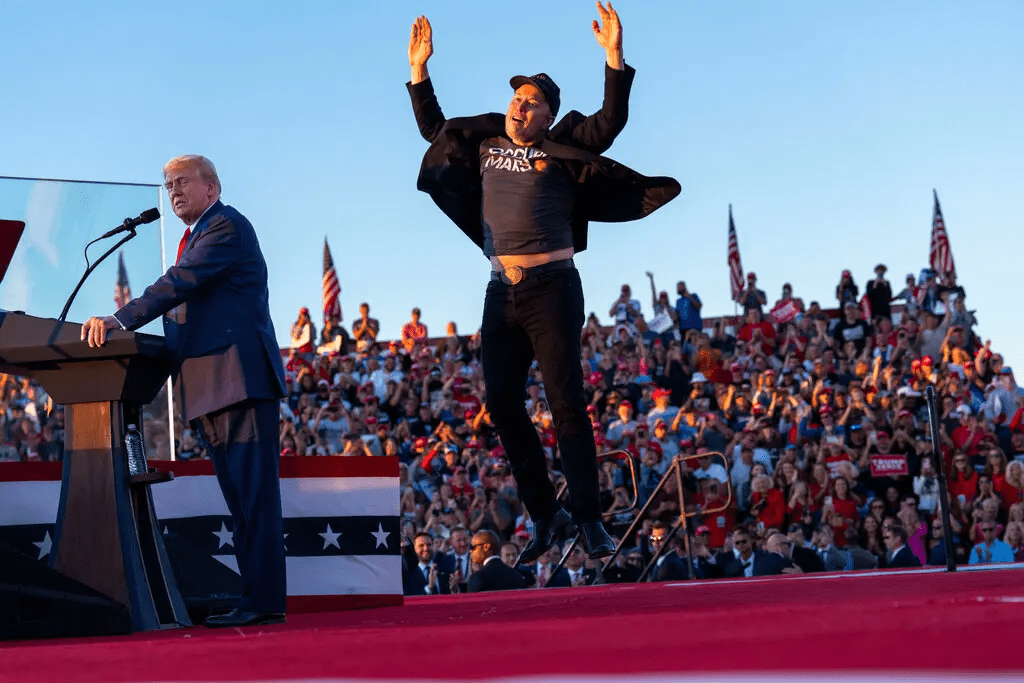

Consequently, writing reviews after a little break feels a little rusty, but I’m gonna give it a go. Elon Musk features in the fifth book I’ve consumed this year, so as long as this ends up reading better than one of his fucking jokes, I figure I’m ahead.

Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez (translated by Megan McDowell).

My rating: four stars.

I received this book in a trade, and had absolutely no idea what it was about. I only knew that the author had written well-received short story collections that looked to be on the stranger side of fiction, but other than that, nothing.

Turns out it was the best way of approaching Our Share of Night because this thing is a fucking cracker, and also Extremely My Kind Of Thing. By which, of course, I mean weird, queer occult lit written by someone who’s extremely culturally aware, has Done the Reading and can spin a yarn that keeps a bunch of plates in the air.

And here begins the part I don’t understand and that, in the part that made me renounce this case and my journalistic instinct, and made me suspect I was at the beginning of a story I didn’t want to know.

Because what happened that day, and the next, is impossible.

The story focuses on generational trauma, spanning time and nations. There’s stints in swinging ’60s London and periods in an Argentina wracked by strongman excesses and disappearing family members. And over all of this (and longer) is the shadow of the Order, a mysterious organisation that courts the knowledge revealed by a dark god. An organisation that has control of the sickly Juan, and has designs on his son, Gaspar. Juan is very keen for his son to not have the life he’s been subjected to, and the story details – from multiple viewpoints – the struggle to find a way to live when you’re marked for something else, something greater, but not in a good way.

Hopefully this would be the only ability Gaspar had inherited. Hopefully he would never achieve the level of contact Juan was capable of.

I’m sure there’s things that I’m missing in the narrative – my knowledge of Latin American history is patchy, to put it kindly – but there’s so much pain in the text that it’s easy to get the broad strokes of suffering without knowing the finer political detail. This book is a long one, but it reads like a short one: compulsively, almost greedily. I absolutely loved it, and hope there’s more long-form fiction in Enriquez’s future, because while I’ll be sure to inhale her short stories in the meantime, I felt the room to stretch out exhibited here really supercharged whatever the fuck it was that was going on.

Recommended.

Comrade Aeon’s Field Guide to Bangkok by Emma Larkin.

My rating: four stars.

I’ve only ever transited through Thailand, so my experience of the country is pretty much zero. The image of Bangkok that’s conveyed in Emma Larkin’s novel, however, makes me feel as if I’ve walked the sweating streets, redolent of hawker food and damp clothes.

The novel tells the story of several individuals and their compatriots: a property developer and his wife (a former actress turned soap-opera scriptwriter), the expatriate wife of a philandering high-flying executive (and their staff), a psychogeographical scribe who walked out of his former life, and a cadre of slum inhabitants. What’s detailed is how their lives interact, despite the shielding of class.

The markings will be incomprehensible to the handful of people who might notice them over the coming days but to Comrade Aeon they convey information critical to the city’s well-being. For years now, he has been walking his song lines across Bangkok and, with great precision and care, annotating the metropolis with his own empirical data.

Characters orbit around a patch of unused ground, close to a slum. It’s ripe for development, a rare place where construction can occur. It’s magnetic: looking down from a rich apartment, it’s a sea of green escapism. From ground level, it’s a potential building. Or it’s home. And across all of it plays the theme song from that new soap that rich and poor alike can’t avoid.

Reading is solitary and secretive, not like watching television, where the story is nicely out in you can follow along with other people and the and open even share a bit of friendly chit-chat as it unfolds. Books she associates with hidden things and if someone is into hidden things, they are almost definitely up to no good.

There’s a dreamy nature to this book that I really liked. I distinctly felt like a tourist, like someone unacquainted with how things worked, and that drove my engagement, mirroring that kind of fantasy bubble that can surround the traveller. There’s gangsters. There’s cats. There’s canals. There’s relationships fraying at the seams, and those striking up in unlikely circumstances.

But there’s also a deadly seriousness at play here: Larkin weaves in Thailand’s instances of overenthusiastic crowd control (i.e., violence and mass murder) at protests, deftly describing how a loss of certainty on the fate of loved ones continues to drain survivors. There’s a deep vein of sadness in the text, with it sometimes seeming like a collection of portraits of people dealing with pain, detailing their search for something to provide liberation or a moment of relief, at least.

There’s a sadness here, but it’s tempered by a love of Bangkok, the sort of affection for a city that makes the reader want to go there. Well, it makes me want to, at least, so that’s something.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton.

My rating: four stars.

I quite enjoyed Catton’s The Luminaries (though it’s about time for a re-read!) and remember preordering Birnam Wood as soon as I heard about it.

(Then, as is usually the case, it stayed on my shelves begging to be read for ages after it actually arrived.)

What’s between these covers is a shorter story than The Luminaries but it’s one that equally conveys a sense of New Zealand. Set in a fictional community on the nation’s South Island (Catton calls out a number of national parks in the area as an inspiration for her Korowai National Park) there’s a vivid, breath-misting portrait drawn of place and its people.

It’s also a psychological thriller about a Peter Thiel-esque billionaire who plans on building a bunker in which he can wait out the end of the world. That makes the book sound a little more guns-ahoy than it is in actuality, but it’s broadly accurate. A guerrilla gardening group – the Birnam Wood of the title – enters the billionaire’s orbit, and things become, uh, complicated.

Everyone’s the same. You reach a certain level and it’s all exactly the same: it’s all just luck and loopholes and being in the right place at the right time, and compound growth taking care of the rest. That’s why we’re all building barricades. It’s in case the rest of you ever figure out how incredibly easy it was for us to get to where we are.

Catton has an excellent eye for detail, and is a piercing critic. The book features finely observed versions of leftist group meetings, rule-bound and territorially-pissed affairs where factionalism seems to be more important than getting shit done. Pride and nationalism is skewered, as is middle class satisfaction, intellectual snobbery and the often uninterrogated boon of personal attractiveness. There’s plenty of nuggets to absorb as the narrative progresses, charting a course around one very rich man’s desires. (In this way I was put in mind of The Rich Man’s House, though that’s probably more a thematic link than anything else.)

Tony had never considered himself to be particularly patriotic – he did not accept, in fact, that there was any material difference between the patriot and the nationalist – and so he had been surprised, and even a little ashamed, to realise just how strongly his nationality had shaped him, not just in his actions and his expectations, but in his political convictions, which he would have liked to think had been formed through his powers of reason and his intellect alone.

The ending of the novel is pretty shocking. I felt a little bit short-changed when I read it – it ties things up very quickly – and while part of me wants to write it off as a bit of a cop-out, it does fit the narrative and how we understand the motivations of the novel’s characters. I enjoyed that I felt a bit of challenge about my take on the story at its conclusion: a sting in the tail, if you will.

Speedboat by Renata Adler.

My rating: three stars.

It’s difficult for me to know what to make of how I feel about this work. When it clicks, it’s diamond-hard, glittering and strong. And when it’s not, it reads a bit like the poetic observations I sometimes write in my Notes app.

(That’s a charitable use of both ‘poetic’ and ‘observations’ there.)

It could be that Speedboat may be another example of a book that I’ve read at the wrong point in my life. (The ur-example of this thus far was Infinite Jest, whose shit I am demonstrably Too Old For.) I just feel like I’m perhaps missing something. Or, more likely, that the chat around the book’s greatness has hamstrung my enjoyment of it: it’s a pretty lauded work, and I think my preconceptions were skewed by some of the discussions I’ve read about it.

That ‘writers write’ is meant to be self-evident. People like to say it. I find it is hardly ever true. Writers drink. Writers rant. Writers phone. Writers sleep. I have met very few writers who write at all.

Adler’s prose is uniformly pretty good. There’s vocab that doesn’t fly today (and causes a bit of an involuntary eye twitch) but on the whole she presents a portrait of vaguely bummed living in New York City in the ’60s and ’70s that’s appealing: that Mad Men type vibe of people holding luncheons, trying to work between hangovers, and experiencing a life mediated by typewriters rather than screens. There’s recurrent characters throughout the book’s spindly frame, and we get an outline of these lives knitted together by the metropolis (and alcohol) in the oblique.

Actually. I know what this is. It’s a bit like a series of tweets, or extended IG stories put into print. Perhaps the genius of Adler that I’m missing is how much work it takes to make something appear so offhand and seemingly throwaway, the observation of seconds rather than a text that’s written, edited and reedited?

I took a little celebrational nap.

Viewed from that position, I think I see the appeal a little more clearly. Give it a read: regardless of my thoughts on structure, the zingers flow.

Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter by Kate Conger and Ryan Mac (read by Edoardo Ballerini).

My rating: four stars.

Allow me to begin by setting the scene with a hearty fuck Elon Musk.

Man, that felt good.

I was a Twitter user for a long time. Not the earliest of adopters, but let’s just say there were decades spent on there – way too much time, as most people who’ve used the now-hellsite fulsomely will tell you – and Musk’s purchase (replete with that fucking sink) basically began the downward spiral into the right wing fuckbakery we now have on our hands. (In case you’re not Terminally Online, here’s Wikipedia’s take on the events the book covers.)

By February 2024, the investment giant Fidelity had marked down the value of X, which was still paying off its onerous debt bill, to $11.8 billion, down more than 73 percent from its $44 billion purchase price.

I finally pulled the plug on my account last year, and while I’m sure fanboys are all it’s not an airport you don’t need to announce your departure it felt both bad and good. Bad, because a place that had been pretty great for a lot of things was now a fucking Nazi bar, and good because I knew that my mental health would improve by not being there any more. (It’s true, it is.)

The billionaire, racked with paranoia, had convinced himself that not all of Twitter’s employees were real.

Character Limit, then, is a book that an online jerk like me would eat with a spoon. It’s the story of Twitter (GTFOH with the whole X thing, guy) from outset to November ’23, when Musk told advertisers to go fuck themselves. It’s the result of extensive interviews and research, and details both the political and financial wrangling behind the billionaire’s purchase of the site (originally as a lame attempt at a joke/impressing his ex-wife, which then became serious because of his lack of due diligence and an unwillingness to realise that shitposting is not something you do with lawyers) as well as providing a barometer of company morale throughout.

(It’s bad. Real bad.)

All the greatest hits are here: that fucking sink. The stupid X sign on Twitter headquarters that had to be torn down within a week. The illegal accomodations inside the office. The rampant staff cuts. The servers being moved like they were regular furniture rather than critical infrastructure.

But the thing that’s most clearly communicated? This fuckin’ guy.

The book reads like an extended version of the I See You about the guy. Sure, we get incredible detail about what other staffers thought and did, and sure, Jack Dorsey comes across like a techbro who’s had too many hits from the bong, but all of the dumbarse ideas, all of the unforced errors: they’re all Elon. He cannot stand criticism, can’t brook the idea that someone might be more popular than him, can’t admit that there’s things he knows fucking nothing about. But he’s got money, so hey. Hubris is going to exact a mighty cost, which is the least the universe can do to someone who called one of their gang of children Techno Mechanicus.

If you’re going to read this book (or cram it in your earholes) then now is probably the time to do it. I’m not sure that it’s the sort of work that’s going to age like a fine wine, unless there’s plans to update the text when Twitter eventually implodes or someone ghost-guns old mate. (Or his ‘meds’ eventually catch up with him, I guess.) It’s the sort of story I’d like to see in its full awful sweep, when things are ended and the ashes cold, but until then: get in while the schadenfreude’s hot.

(Once more, fuck Elon Musk.)

If you’re after some good bookish times, please check out my profile on TheStoryGraph.

If you’d like to buy me some books to review, there’s a wishlist over here.